Blog post by Geordie Hall

Geordie is an under-graduate student at the University of Exeter. He is undertaking a placement at the Corinium Museum as part of his module on Public History. Geordie contributed this blog as part of his placement experience, A Reflection on Animal History at the Corinium Museum.

For much of human history animals have been regarded as one of the following;

1. Beast of burden

2. Predator

3. Prey/Game

4. Pet

5. Livestock

They have been seen as ever present, but not terribly significant outside of a purely utilitarian sense; Can we eat them, wear them or ride them? If the answer is no to all three questions, then the average historian usually doesn’t have much more than a cursory interest in how these creatures have impacted human history, nor in how significant said humans thought them to be, either in the aforementioned utilitarian sense or, in certain contexts, a more spiritual/artistic one. The Corinium’s collection, however, holds several items that showcase how important animals have been in the history of Cirencester, Rome and Britain.

Beginning with the Neolithic Deer Antler Picks discovered at the Hazelton North Long Barrow. On one level this is still purely utilitarian, a tool used by early man, but, flipping that reasoning, what would have happened to its Neolithic users if there were no deer? Did they have access to alternative materials that could have provided the same results? If the answer is no, then the absence of one single species would have been enough to hold back an entire community of humans, simply by default. The tool may be basically utilitarian, but the deer’s presence and interaction with early man was key to mankind’s development of tools in Neolithic Britain.

A less utilitarian side is seen in the dog skeleton unearthed at Kingshill, North Cirencester. The dog appears to have been intentionally buried with someone, presumably its owner, which raises certain questions; was this dog a pet? If so, then the grave may mark nothing more than a particularly sentimental dog owner, but that seems unlikely on two points; firstly, dogs at this point in history are difficult to describe as ‘pets’. Domesticated? Certainly. But early European dog breeds were still fundamentally working dogs and it seems unlikely that someone would wish to be buried with one, unless one considers the second point, that people in these early societies usually chose the items in a burial plot with great care and for specific, culturally significant, reason. Therefore, the dog is more likely to have a spiritual meaning as part of some funeral rite or ritual. What can easily be dismissed as someone buried with their favourite pet and nothing more could in fact be evidence of dogs in pre-Roman Britain having a religious significance that merited inclusion in a burial.

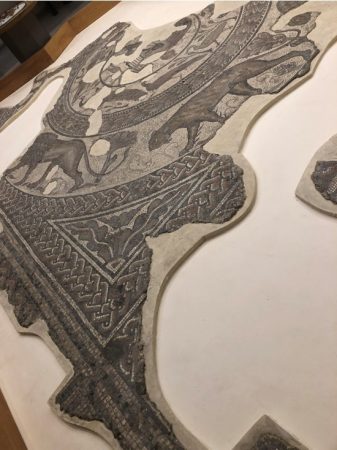

There is a fine line between religious and artistic significance, and the Romans certainly included animals in their artworks found in the Cotswolds, the Orpheus Mosaic being a prime example of a focus on animalistic imagery. We can presume such imagery would have at least been widely understood by educated people in Roman Britain, as there would seem to be little purpose to commissioning such a work if there wasn’t at least a chance that people would understand it and themselves ascribe some meaning and significance to the animal figures.

he utilitarian importance and artistic significance of the animals come together in the form of the Cirencester wool trade/industry, exemplified by the superb specimen of a ‘Cotswold Lion’ as well as several replica brasses showing lambs and sheep as motifs. Roman-era Cirencester had been one cog of a wider imperial machine, and its place in the world has not long survived the machines demise, but through the wool trade, Cirencester became rich, powerful and famous across Western Europe for its wool exports. The sheep (or Cotswold Lions) allowed Cirencester to develop as a settlement and community after the collapse of the Roman infrastructure that had previously sustained the town, and in doing so acquired a local cultural significance that earlier animals were often denied, or when not denied, was simply forgotten about.

Animals have played a unique part in the shaping of human history, an often overlooked one, but these items at the Corinium Museum can hopefully show their importance now.