Blog post by Teddy Lewis

Teddy Lewis is a recent Ancient & Modern History graduate with a focus on the Late Republic and early Empire.

Glassworking had a long history before the Romans. Hellenistic glass workers would make bowls and cups by ‘sagging’ molten glass into moulds and items with hollow insides such as jugs and vases using a technique called ‘core-forming’. The glassmaker formed the glass into shape around a removable core of fired clay the same shape as the inside of the vessel, either by dipping the removable core into liquid glass or by rolling it repeatedly in powdered glass and heating it to build up the outer wall. Once the glass was formed, decorated, and cooled, the clay core had to be scraped out from the vessel. This left a cavity often used to hold unguents and perfumes. Many of Rome’s early techniques were inherited from Hellenistic practices until the invention of glassblowing on the Levantine coast in the mid-first century BCE. This new technique inflated molten glass into a hollow vessel by blowing air into it through a tube, thus creating a cavity without the need for core-forming.

The vast majority of glass produced in the Roman world was natron glass, which was made by fluxing a suitable sand with natron and stabilising it with lime, although a small number of samples have been recovered that were fluxed with plant ash instead. Cheaper glass was often bluish-green, but it could be made colourless by clarifying the glass melt with antimony oxide. Glass could also be coloured by adding minerals such as cobalt, copper, and manganese during production. ‘Suitable’ sands were relatively rare; analyses by the ARCHGLASS Project found only around 6 sources of sand across the empire with a suitable chemical composition for Roman glassmaking, even including ones that would have required an additional source of lime. Pliny the Elder identified the best source as sand from the river Belus in Phoenicia, and wrote that for centuries glass production depended on this area. Given the very limited sources of suitable materials for natron glass it is likely that raw glass was produced in a small number of centres and then transported across the empire to be worked into finished products by artisans, although some academics argue in favour of localised glass production.

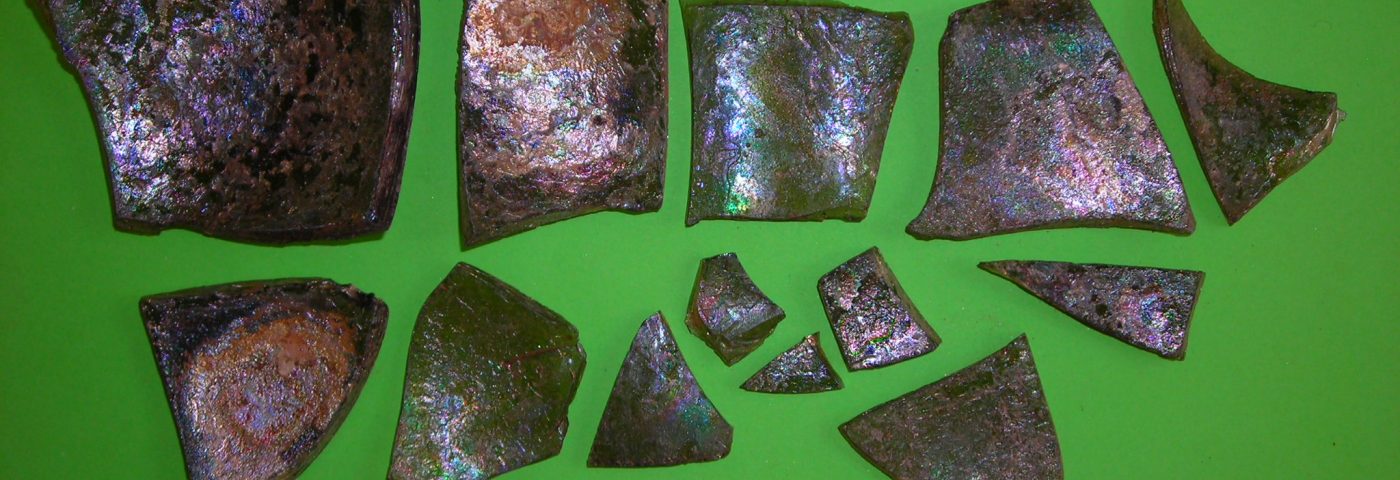

Hellenistic glass was expensive and highly decorative, however by the first and second centuries CE glass as a material had become relatively cheap. Its increasing affordability may have taken place as early as the turn of the 1st century CE; the Roman geographer, Strabo, mentions that “there have been many inventions both for producing various colours, and for facilitating the manufacture, as for example in glass wares, where a glass bowl may be purchased for a copper coin, and glass is ordinarily used for drinking.” (Strab. 16.2.25) The invention of glassblowing allowed Roman production to significantly increase and to spread — archaeological evidence for glass workshops has been found all over the Empire, including 20 excavated in Britain. This made ‘mass-produced’, pale green-blue blown glass like the fragment pictured below widely available across social classes. Glassware could still be a luxury depending on its style and decoration. Another development in Roman glassworking was the creation of cameo vessels, such as the Portland Vase, where glassware was dipped into a contrasting colour (in the case of the Portland Vase, the base is blue and the cameo is white) and then the contrasting colour was carved away to create a relief. Wealthy Romans preferred glass dinnerware to metal or pottery because the latter were said to give off an unpleasant smell, particularly in the heat of summer, whereas glass was odourless — in Petronius’ Satyricon Trimalchio says: “you will forgive me if I say that personally I prefer glass; glass at least does not smell.” (Petr. 50)

Fragments such as this would have formed part of cups, bowls, jugs, and dinnerware, however glass was used in a variety of applications in the Roman world, particularly as it became more ubiquitous and less expensive. Glass was also used to make beads, jewellery, amphorae for transporting goods, perfume bottles, and tesserae (small pieces of coloured material used to make mosaics). Coloured glass could be used to imitate gemstones — blue for lapis, red for Jasper, garnet, or carnelian, yellow for topaz — which were a cheaper alternative for items like carved intaglio rings. For example, Pliny the Elder references “the glassy paste which the lower classes wear in their rings” (Plin. Nat. 35.30), as carved rings were usually made out of semi-precious gems. Glass became a common material throughout the Roman world, put to a variety of uses and available to a great number of people.

References:

- The Art Institute of Chicago. (2013). LaunchPad: Ancient Glassmaking—The Core-Formed Technique [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9RaWUbnOF1o

- Henderson, J. (2013). Glass as a Material: A Technological Background in Faience, Pottery and Metal? In Ancient Glass: An Interdisciplinary Exploration (pp. 1-21). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139021883.002

- Scott, R. B., & Degryse, P. (2014). The archaeology and archaeometry of natron glass making. In P. Degryse (Ed.), Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World: Results of the ARCHGLASS project (pp. 15–26). Leuven University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2bctjr.6

- Brems, D., & Degryse, P. (2014). Western Mediterranean sands for ancient glass making. In P. Degryse (Ed.), Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World: Results of the ARCHGLASS project (pp. 27–50). Leuven University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2bctjr.7

- Strabo, Jones, Horace Leonard, & Sterrett, J. R. Sitlington. (1917). Geography (Loeb classical library; 49-50, 182, 196, 211, 223, 241, 267). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. (1855). The Natural History. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street.

- Petronius Arbiter, Seneca, Lucius Annaeus, Heseltine, Michael, Rouse, W. H. D, & Warmington, E. H. (1913). Satyricon (New ed. / revised by E.H. Warmington. ed., Loeb classical library ; 15). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.