Join Collections Assistant Dr Caroline Morris as she explores the Museum stores.

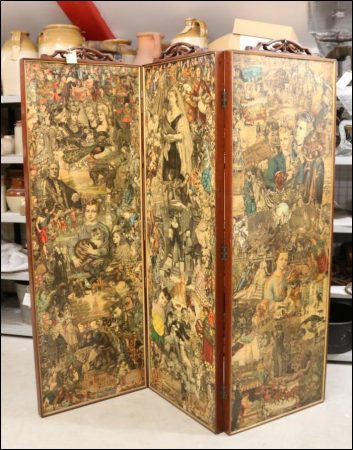

During one of my explorations of our stores, I peeled back the corner of some tissue and discovered a wonderful thing – well I think it’s wonderful. Poking out from the tissue were a pair of eyes and as I peeled it back I was confronted by the face of a woman and child – a print, cut out, pasted and varnish. As I unwrapped the whole thing, it revealed itself to be a three-fold screen; each panel of which was covered in images, carefully arranged. Back at the museum, I found the cataloguing record which told me a little more about it; an approximate date of the 1880’s and that it had been made by F.A.Trinder’s mother. I knew we had quite a number of objects in the Trinder collection so I endeavoured to see if I could discover a little more about Mrs Trinder and the screen.

The photographic collection gave me a lead with a family portrait and then I could give a face to the screen’s maker. Eliza Trinder was married to Joseph, who ran chemist near the church in Cirencester market place. They had five children, Joe, Garnett, Frederick, Constance and Ethel. Frederick would later go on to run a successful newsagents on Castle Street from the 1920’s until the early 1980’s. It was from his shop and home that the museum’s Trinder collection came. An 1891 census record that we had in the collection’s file also told me that the family kept a maid called Emily, then aged 21. The Trinder’s were a successful middle class family.

The making of ‘scrap’ screens had been a ‘suitable’ occupation for a lady since the late seventeenth century, but then it had been an activity for the upper classes with money and time on their hands. By the nineteenth century, the increased availability of printed materials and the rising affluence of the ‘middling sort’ meant that this suitable occupation filtered down the social scale. How much spare time Eliza would have had with four very young children to look after if she had not had her maid – with success came more money and staff, and with that came time for recreation.

Cassell’s Household Guide of 1869 (subtitled – being a complete encyclopaedia of domestic and social economy and forming a guide to every department of practical life) includes scrap screening instructions in an article called ‘Recreations for Long Evenings’. As a popular household guide it is possible that Eliza may have seen this, or something similar.

“Preparing scraps to cover a screen is an employment that fills up a good deal of spare time, entails no mental exertion, and may be done at small expense, beyond that for the mere frame of the screen, which, with a simple covering of black paper will cost about a pound, and if the scraps are arranged upon it with any amount of taste and judgment, a very attractive addition will have been made to the furniture of the room, and one that at the same time may be found exceedingly useful, as a protection against draughts, or the excessive heat of a fire.”

Much is made in Cassell’s article about scrap screens as an expression of style and taste. Whether the maker adds images with careful space left between them or ‘pell mell’ to make interesting juxtapositions. Although it was thought “…desirable not to choose too many pictures representing the same class of subjects; there should be a judicious assortment of figure subjects, landscapes, animals, fruit, and flowers“.

The figure that dominates the screen is Queen Victoria. A large regal illustration on one panel, a more intimate one of the Queen and her consort on another, with the Albert Memorial and Albert Hall arranged below. Most of the remaining people, of which there are many, I could not recognise. Interestingly, one of the panels has a number of sepia photographs included and I wonder if they are friends or relatives of the Trinder family. Photography was much more accessible in the late nineteenth century; some of these may have come from cartes de visite or perhaps from Dennis Moss’ studio on Castle Street.

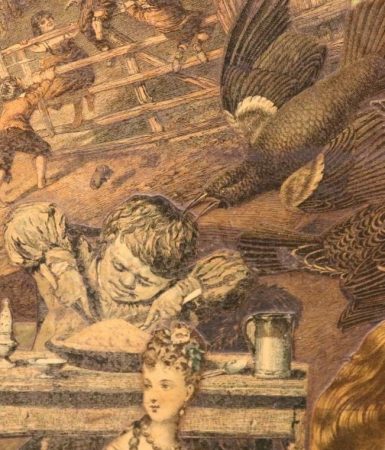

On close study, Eliza’s ‘judicious assortment’ includes, alongside the sentimental scenes so popular with the Victorians, elements of Victorian humour. This is something which Cassell’s recommends to its readers. Comic arrangements may be got “…for instance, by putting into a landscape small figures grouped in a valley as a picnic party, or climbing a mountain, or walking about the features of other figures much larger. One may cut out an umbrella and place it as if held by a duck, or transfer a pair of spectacles to the countenance of a lion.”

The following are examples of this ‘comic’ arrangement – possible less potentially amusing to modern eyes than they were to Victorians, but they are examples of Eliza’s more whimsical arrangements.

A boy about to lose his dinner to a bird

The hand of the man resting on that of the boy whilst the dog inches closer to the grapes.

A dog looking up the skirt of a lady.

A blue cat’s head pasted onto a hunter with a gun.

There is so much more I could write about in this intricately made screen that I might have to do a part two…

Comments

I am related to the Trinders so am pleased to find this article. I hope to try and get to the museum sometime.