Blog post by Holly Foster

To his music plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

— William Shakespeare, Orpheus

Orpheus is a popular figure in mosaic art from the Roman Empire. He’s often depicted playing the lyre given to him by the god Apollo, which Orpheus famously used to soften the heart of Hades and attempt to retrieve his wife, Eurydice, from the underworld. His mythic departure from and return to the land of the living was only possible through his divine ability as a musician to charm beasts, move mountains, and bring harmony to the natural world.

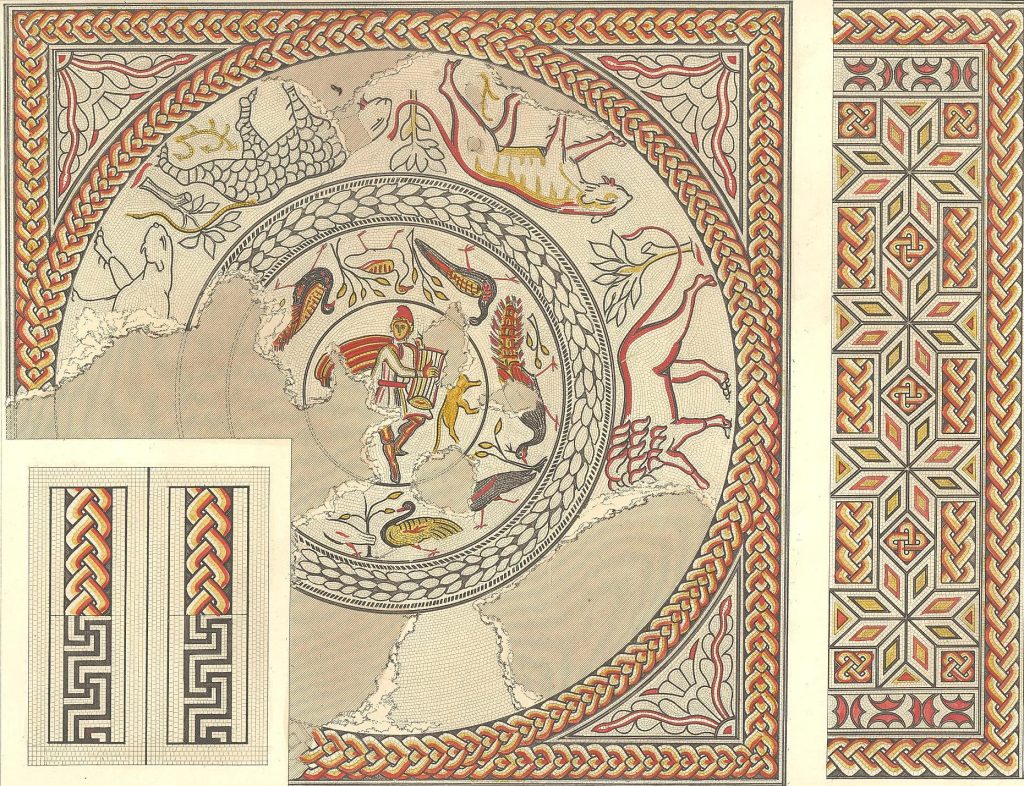

Corinium Museum Orpheus mosaic illustration

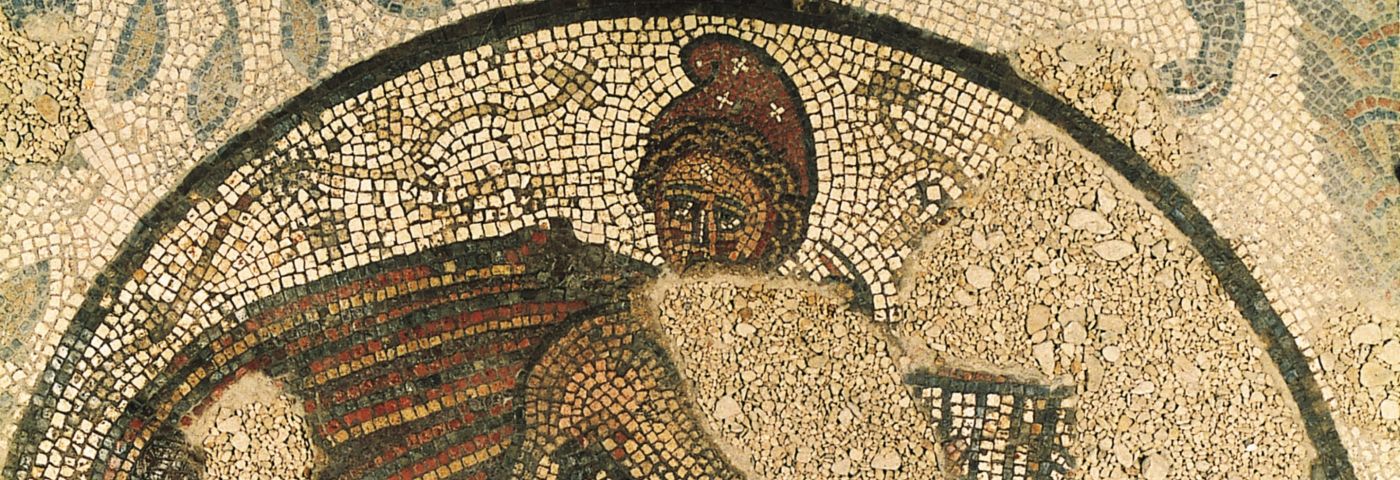

This Orpheus mosaic was found near Cirencester at Barton Farm. Orpheus and his lyre are placed in a central medallion which is circled first by birds, then by large cats in shades of red and yellow. The animals prowl between stems and saplings, all springing towards Orpheus as his song soothes, enchants, and unifies. It’s a vibrant example of Roman craftsmanship and reflects the wealth of the fourth century settlement at Cirencester. In the south-west, many mosaics have been uncovered in country villas and townhouses, marking the area as a prime channel of Romano-British culture and life.

When paved on the floor, the mosaic’s circular design allows it to be viewed and understood from every angle, with Orpheus always placed at its centre. The position of Orpheus is primarily suggestive of his power over the natural world. Wild animals surround him in concentric circles, bound by both the influence of his music and the mosaic’s braided borders. The gentler characterisation of Orpheus’ control over nature sets him apart from other animal scenes depicted in Roman art; his power is achieved through his artistry, rather than through acts of physical strength or violence.

In fourth century artwork, the representation of a harmony between all beings may have made Orpheus a particularly popular figure. He reveals how minds and worlds can be continually transformed through art, not only in centuries of retold myth but in the endurance of the Orpheus mosaics. Rather than power, we may instead see a figure defined by his phenomenal potential for imagination. The vision of a united world is one that I’m sure all of us in 2021 can appreciate. And, with Spring only months away, we might still be able to hear Orpheus’ immortal song binding us together, even now as we stay apart.

Blog post by Holly Foster

Holly grew up in the Cotswolds and loved learning about its rural history at the Corinium Museum. She is now an Anthropology postgraduate from the University of Kent, specialising in European culture, art, and literature.

Bibliography

Jesnick. I. (1989). Animals in the Orpheus Mosaics. Mosaic (16), 9-13.

Meinert, K., Keiner, E., and Bak, A. (2019). Symbolism in the Allegory: A Look at Apollo’s Lyre. Festschrift: Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo.

Neal, D. S. and Cosh, S. R. (2009). Roman Mosaics of Britain. Volume III. London: The Society of Antiquaries of London.

Scott, S. (1995). Symbols of Power and Nature: The Orpheus Mosaic of Fourth Century Britain and Their Architectural Contexts. Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal (14), 105–123.