Isobel is one of our summer intern placements. She is currently studying at Utrecht University and has an interest in the classical world.

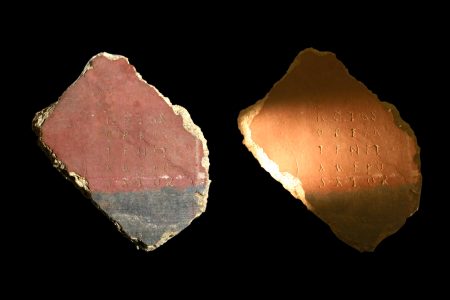

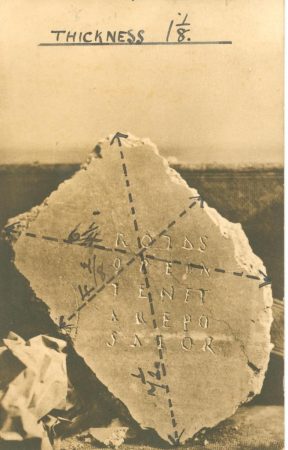

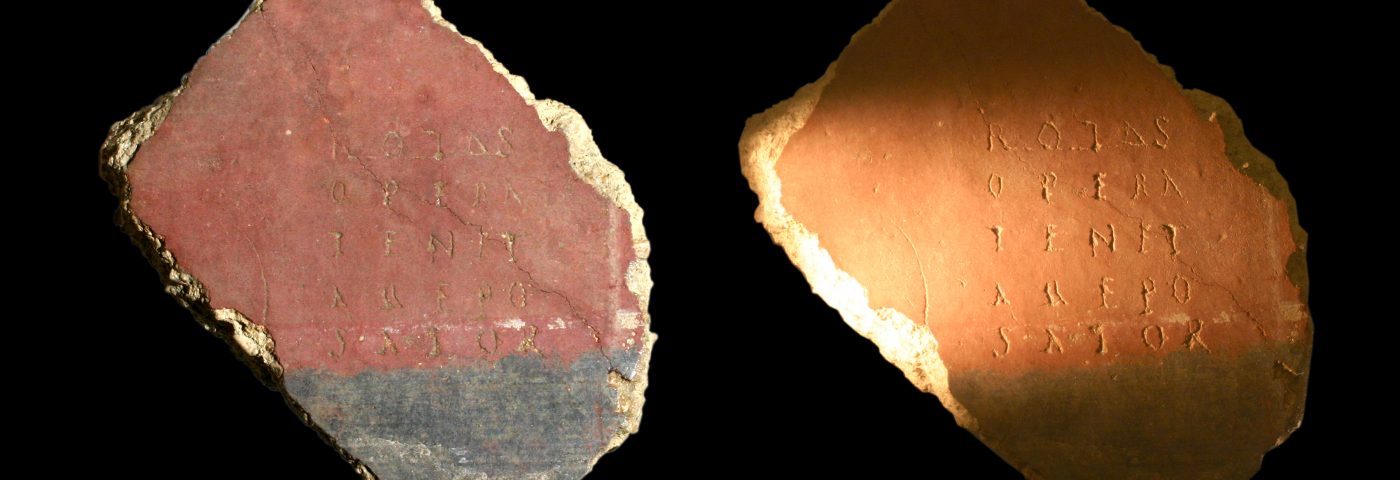

This acrostic is an example of a second century CE Sator Square carved into a painted section of wall plaster, which was excavated from a Roman house on Victoria Road, Cirencester in 1868 during the levelling of a contemporary garden, amongst coins and tiles.

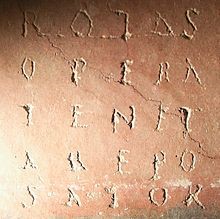

Sator squares are acrostics in which letters are mirrored left to right, up and down, and back to front. The Sator square is an ancient palindrome, its text reading:

R O T A S

O P E R A

T E N E T

A R E P O

S A T O R

Sator squares are keenly debated and disputed by scholars, and their appropriate translation is often part of these discourses. A common translation takes the elsewhere unattested word ‘Arepo’ as a masculine proper name, rendering the Latin in English as something along the lines of ‘Arepo the sower (sator) guides (tenet) the wheel (rotas) with skill (opera)’. Although there are many variations with their own nuances, this standard form of translation suggests that, at least on the surface, Sator squares convey information about a dutiful farmer named Arepo and the nature of his work.

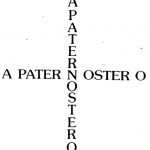

There are several instances of medieval Sator squares, and a handful which have been dated to antiquity: two from Pompeii, which must have been inscribed before 79 CE, as well as ancient instances of the Sator square from Dura-Europos, modern-day eastern Syria, one from Deansgate in Manchester, and this one from Corinium. Before these antiquities were excavated or dated, the medieval Sator squares had already been related to Christian practices. Rearranging the eight Latin letters around the central N reveals the anagram PATERNOSTER in the shape of a Greek cross, Latin for ‘our father’ and accordingly the first two words of the Lord’s prayer. This transformation of the form of the square leaves two letters A and O spare, which are considered to represent the Greek alpha and omega, which also have great Christian significance (Revelation 1:8: ‘I am alpha and omega’). Even the subject of the code has Christian connotations, with the reference to a sower (‘sator’) invoking biblical discussions of seeds, reaping, and sewing, such as in Zechariah 8:12 and Matthew 13.

There are several instances of medieval Sator squares, and a handful which have been dated to antiquity: two from Pompeii, which must have been inscribed before 79 CE, as well as ancient instances of the Sator square from Dura-Europos, modern-day eastern Syria, one from Deansgate in Manchester, and this one from Corinium. Before these antiquities were excavated or dated, the medieval Sator squares had already been related to Christian practices. Rearranging the eight Latin letters around the central N reveals the anagram PATERNOSTER in the shape of a Greek cross, Latin for ‘our father’ and accordingly the first two words of the Lord’s prayer. This transformation of the form of the square leaves two letters A and O spare, which are considered to represent the Greek alpha and omega, which also have great Christian significance (Revelation 1:8: ‘I am alpha and omega’). Even the subject of the code has Christian connotations, with the reference to a sower (‘sator’) invoking biblical discussions of seeds, reaping, and sewing, such as in Zechariah 8:12 and Matthew 13.

However, there is less consensus and certainty about the relation of Christianity to the ancient Sator squares. Were they always secret Christian devotions to ‘our father’, the alpha and omega, or were they a magical and symbolic ancient word game later adopted by Christians? Evidence for the latter interpretation includes the dating of each extant and excavated example of a Sator square: although all of them were produced in the Common Era and after the development of the Christian faith, they would all have been notably premature references to Christianity in their respective findspots. The Sator square in Pompeii can have been produced only around 40 years after the estimated death of Christ, which would make it a remarkably early instance of a Christian talisman. The same is true of the Sator square excavated from Dura-Europos, as well as for the two British examples dated to around the second century CE, long before widespread Christianity in the British Isles and only just coinciding with the earliest traces of Christian faith on the island, around 180 CE.

On the other hand, there is a fascinating prospect that these acrostics have been tied to the secret worship of Christianity from their inception. The interpretation that they do represent a devotional code suggests that they must have been designed to do so, and their attestation only to after the death of Christ reaffirms this possibility. Until late antiquity, Christians in the Roman empire were persecuted, repressed, and often worshipped in secret, creating hidden signs, and engaging in confidential practices such as these Sator squares. This would have been the case for the Romano-British inhabitant of Corinium who inscribed this acrostic into the painted wall of their home.

Besides the Christian connection, various scholars have hypothesised other explanations for the existence and prevalence of Sator squares across the area of the Roman empire. It is equally possible that one of these interpretations is responsible for the second century carving of this Corinium Sator square by a Roman Briton. There is general academic consensus that the presence of Christianity in Pompeii before 79 CE is improbable, and there are other factors which suggest early Roman examples such as the Pompeii and Corinium Sator squares were not originally Christian: the cross did not become a popular motif of Christ until well into the second century CE, the concept of God as the alpha and omega was also popularised later, Greek and not Latin was the common language of Christianity during this period, and cryptic Christian symbols are more closely related to the periods of their widespread persecution, notably from the third century. Thus, it is possible that the early examples of Sator squares were not tied to Christianity but rather recycled and reappropriated by later Christians after their rediscovery or re-popularisation throughout the medieval period.

But if the Pater Noster cross was not always the hidden meaning of a Sator square, what were they originally created for? These puzzles have been found across the Roman empire from antiquity to the Renaissance, with examples from Sweden to Syria. The religious imagery of a sewer as the creator, as well as the mysticism of an elusive palindrome, has attracted countless groups throughout the lifespan of Sator squares, which have been appropriated by modern film directors and Pennsylvanian Dutch healers – who inscribed the Sator square on butter bread and fed it to patients with rabies – alike. The origins of the square are disputed, meaning that the cryptogram remains a mystery, but various explanations are offered. The Sator square has been related to the Roman cult of Mithras, as well as to ancient Judaism. Interpreting the palindrome as a mathematical equation suggests that it represents the Jewish divinity. On the other hand, ‘sator’ was used by Romans to describe Jupiter, the king of the Roman gods and their heavenly father accordingly comparable to the Christian ‘pater noster’. Therefore, the square could have indicated piety in Roman paganism all along. Scholars of medieval Sator squares do not doubt their relation to Christianity, attested by their provenance, contexts, and contents, however the issue of their original significance is more controversial and uncertain; work still needs to be done to decode this two-thousand-year-old mystery, to which Roman subjects in Pompeii and Corinium held the lost key.

So, what does this Sator square find mean for our modern understanding of Roman Corinium? Could it be evidence of early Christian worship in the Roman town? If so, this find would be highly significant for modern understanding of early Christianity in the Roman empire, and in the British Isles. But even if this Sator square cannot be linked to second century Christianity, its existence is no less captivating and consequential. The Corinium Sator square is evidence of identical mystical practices spanning from Syria to Italy to southern and northern England, which spread with the conquests of the Roman empire and extension of the Latin language, contributing to the common culture of the Roman world. Today, the acrostic square remains open to interpretation and contentiously considered by scholars and is still just as mysterious as its inscriber likely intended for it to be almost two millennia ago, whether because they were closeted Christians or participants in a practice imbued with mysticism which connected Roman subjects across the empire.

Blog by Isobel Wilkes

Comments

Jewish Essenism ( Herods mission) becoming Christianity after AD44 had become increasingly popular in Roman Empire in 1st century AD.

Both Agrippas (Acknowledged Jewish Kings from Judea) were welcomed at Roman court

Nero blames them ( Christians) for fire in Rome AD64. Tacitus

See “Jesus the Man” by Barbara Thiering

Not sure why everyone seems intent on forcing a translation of the wrong words.

The right five words to translate are:

Sat

Orare

Potenet

Opera

Rotas

Sufficient prayer can turn the wheels (of the world).