This month’s blog entry coincides with a new display at the Corinium Museum which looks at agriculture and food production.

Caitlin Greenwood is a current PhD student at the University of Bristol. She is working on extracting food residues from Roman pottery stored at Corinium Museum.

Why Food?

Brilliant historical food writer, Jean Anthelme Brillart-Savarin once said “tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are”. Food is not just the calories human beings need to survive, it’s also a way we express ourselves. Think about what you would and would not eat: many bugs are edible, would you eat them? What about dog meat? Horse meat? Cow meat? These ideas are defined by our cultural ideas about food (our foodways) rather than by what is biologically possible.

Food also tells us about boundaries, both within our society and without. In the first ever English dictionary Dr Johnson defined Oats as “A grain which in England is generally given to horses but in Scotland supports the people”. You can feel the boundary there, can’t you? We only feed oats to our horses but those people are so poor or primitive or backwards that they eat oats. Similarly, the Roman geographer Strabo mocked the ancient Britons by saying that, though they had milk, they could not make cheese.

Finally, food is a really important part of how we relate to each other. Commensality, the act of sharing food and drink, is embedded in almost every human culture and is a major topic of study to anthropologists, social scientists and ethnographers. If you tell us how and with whom you eat, we can tell you what you are.

How does it work?

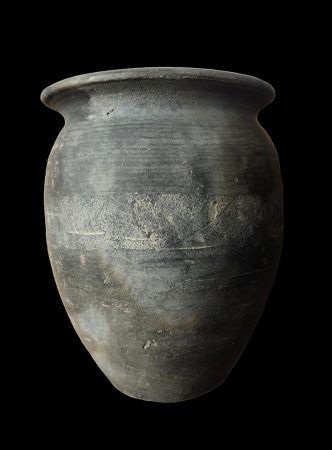

Organic residue analysis (ORA) works by extracting food residues from inside the matrix of pottery. Before the invention of glaze, pottery was not completely water (or food) proof, so during storage and especially cooking some of the molecules in the food migrate into the pot and stay there. These can be extracted from the pot fragment in the lab and then analysed. The most common molecules to survive are fats and oils (known as lipids in chemistry) because they are so water insoluble (Think about how much harder it is to clean a frying pan than a plate when you’ve run out of washing up liquid). By analysing these fats, we can say whether they were from plants, ruminant animals like cows or sheep, dairy fats from milk, cheese or butter, or non-ruminant animals like pigs. From one pot, this wouldn’t be very interesting but from 100 (or 700, which is my goal) we can hopefully start to see overall trends in diet that would otherwise be archaeologically invisible.

What will it tell us?

My hope is that by looking at a range of different sites, cities, farms, small towns and villas, over the whole of the Roman period emerging trends will allow us to know more about what life was really like for people in Roman Britain and what it meant to be a subject of the Roman Empire.

Watch this space for a later post about food in Roman Cirencester!