Alexander Neckham was born in St. Albans in 1157 of aristocratic parents on the same day as Richard the Lionheart was born in Windsor. As was customary at that time, the Royal baby was immediately fostered onto a nursing mother – Alexander’s mother, Hodierna (it is probable that Hodierna Knoyle (now West Knoyle) in Wiltshire is connected to the family.) Hodierna must have known the great Eleanor of Aquitaine. There is evidence that Hodierna had favour with the Royal Family as she received a substantial pension from Henry I which was still being paid to her by King John. So it is reasonable to suppose that Alexander also had Royal favour, which was important when King John was levying severe taxes, including on Abbeys, to fund his conflicts with France: Cirencester Abbey seems to have been excused.

Neckham was educated at the school at St. Alban’s, one of the oldest of all schools, founded in 948. Later Neckham was himself a Master at St Alban’s and he also taught at Dunstable, Bedfordshire, which was under the control of St Alban’s Abbey. By 1180 he was in Paris, “at this time the goal of all students in the arts and theology” (Hunt R. W. (M. Gibson ed) The Schools and the Cloister. Clarendon Press. 1984)

At some point the young Alexander agreed with fellow students that they should eventually enter into monastic life. The received attitude to theological study was to interpret the Church’s teaching in the light of thought rather than observation. It was the re-discovery of the Greek classics via the Arab world and translations into Latin that stimulated the Twelfth Century Renaissance. This movement followed Aristotle: Neckham calls him “the great, the most acute Aristotle, the most excellent philosopher, the guide, the head and honour of the world”. But Aristotle was a pagan and there is a hint that Neckham was uncertain of how the Church would react to this new approach and in his Commentary on Ecclesiastes he suggests that these books should be studied discreetly.

By 1185 Neckham had secured the post of Master at the school in St. Albans. To obtain this position he had written to Abbot Garinus who replied in a pun on Neckham’s name : Si bonus es uenias; si nequam, nequamquam : If you are a good man, come: if worthless, by no means.

It was during this period in his life that he wrote two works revising fables : Novus Esopus (Aesop) and Novus Avianus ( a Latin writer c 400 AD). In lessons on rhetoric schoolboys were required to analyse fables, giving them a moral interpretation and create their own. One of Neckham’s own is included in his Novus Esopus. “A gnat settled on the horn of a bull, and sat there a long time. Just as he was about to fly off, he made a buzzing noise and enquired of the bull if he would like him to go. The bull replied, ‘I did not know you had come, and I shall not miss you when you go away’.”

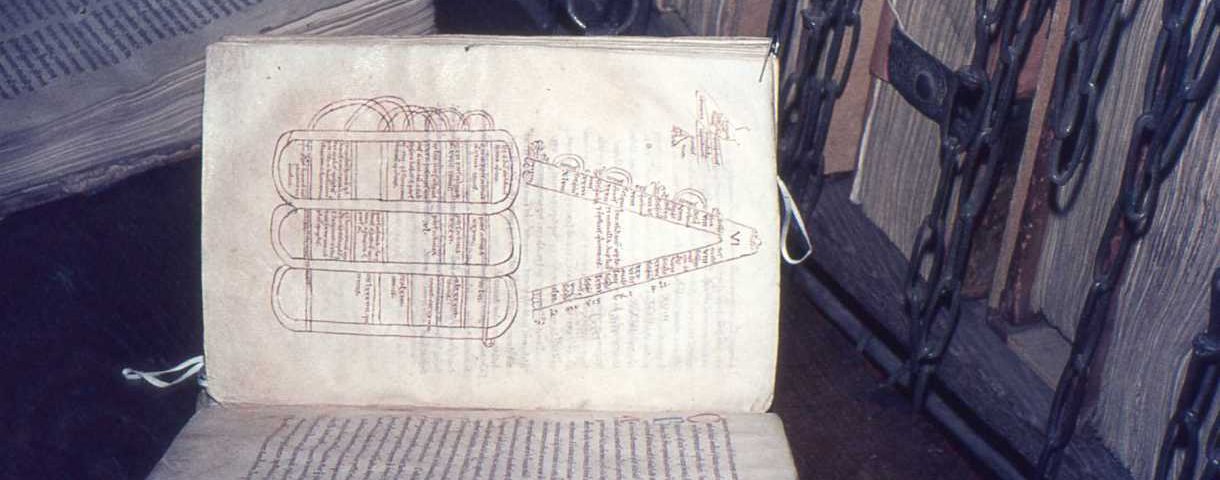

It was also at this time that he wrote De nominibus utensilibus (On the names of useful things) for his students (see Bodleian Digby 37 on display).

Neckham entered Cirencester Abbey between 1197 and 1202. Had he become tired of the need to attract scholars? Masters at the centres of higher learning needed entrepreneurial endeavour to earn their living: pupils brought fees. On the other hand, it was a common decision at that time to enter a monastery late in academic life to have time to consolidate one’s studies. Some of his academic colleagues tried to dissuade him from fulfilling his youthful pledge to enter a monastery: “But he became like a deaf man and heard not the sounds of the world.” Peter of Blois, Archdeacon of London and one of his friends, congratulated him on his decision. However, we should not think of Alexander as a dour ascetic. He had a reputation for making jokes including practical jokes. When he was once asked to keep a sermon short he made it just one sentence long. He also liked to have a glass of wine, which he tells us is to be preferred over beer, beside him while he wrote. Why did Neckham choose Cirencester Abbey? Perhaps because he knew of it from conversation with Robert of Cricklade in the Augustinian House in Oxford. It has been suggested that he knew that Cirencester Abbey had an excellent Library such as a scholar would need. The medieval emphasis on the importance of books is summed up in the aphorism: “A cloister without books is as a castle without an armoury.” The value set on books is clear from such curses as this: “For him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not this book to its owner, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with palsy and all his members be blasted. Let him languish in pain crying out for mercy and let there be no surcease to his agony till he sink in dissolution. Then, let book worms gnaw his entrails and when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of hell consume him – for ever.”

During his early years at Cirencester Abbey Neckham is referred to as “Master Alexander” which may mean that he continued his work as teacher in the post of Headmaster of the Abbey School.

Amongst the books Neckham would have found in the Abbey Library was De templo (On the Temple) (see Jesus College 52 on display)

It was also in his time as Canon/ Master Alexander that he wrote De rerum naturis (On things in nature).

Subjects covered in this and others of his works included astronomy. “The sun is a hundred and sixty times and a fraction larger than the earth”. Neckham also wrote about plants including herbs which were the foundation of medieval medicine and grown in the Abbey garden. Both Herbals and Bestiaries were available at this time but Neckham seems to have implemented the new approach to scholarship and, from actual observation rather than received opinion, corrected many errors even omitting some of the more fantastical notions of such writers as Gerald of Wales (1188). He also suggested that gardeners should try to see if they could get plants to grow, another indication of Neckham’s encouragement of an inquisitive mind.

In 1213 Neckham produced Laus sapientie divine (The praise of divine wisdom) a versified version of De naturis rerum which shows his continued interest in scientific matters including the stars and the elements. Three years later, shortly before he died, Neckam wrote Suppletio defectum (Supplying defects or ammendments …to Laus sapientie divine) in which he writes about birds and other animals and gives descriptions of trees, herbs and other plants. Here he also reveals that the concern over the calculation of the date for Easter was still current : there are still, he says, “manifest errors in the vulgar compotus”. “The love of knowledge” he writes “is naturally implanted in the human mind. Hence it aspires to an understanding of it. It seeks out the cause of things,” (Hunt op cit) reminding us of Neckham’s involvement in the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the new theological thinking.

Neckham was elected Abbot in 1213 in the presence of King John. He already had experience in the administration of his Abbey as he had been appointed by the Bishop of Worcester to oversee Abbot Richard under whose Abbacy a Visitation by the Bishop and the Archbishop had revealed mal-administration. Neckham was also an ecclesiastical judge and appointed as a papal judge. In civil matters he acted for King John in examining the rights of the Augustinian Priory of Kenilworth. During 1208-1214 England was placed under interdict by the Pope Innocent III when King John refused to accept the Pope’s nomination of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. An Interdict had great effect on the Church and the People : public services were banned, the appointment of new bishops suspended. It is mark of Neckham’s reputation that he, along with his friend Peter of Blois and others, was used by the King to negotiate with the Pope. Royal records of King John’s reign include: “May 1213 – Henricus de Alemannia – 15 pence for taking some letters to Alexander at Cirencester.”

It was during Neckham’s time as Abbot that the Abbey regained some of its lost rights in the Seven Hundreds (the extensive area in the Cotswolds over which the Abbey had gained control) and also obtained the right to an annual market over the eight days of All Saintstide. It is not surprising that administrative concerns meant that Neckham’s scholarly output now fell away. And yet it was as late as 1213/5 that he wrote his major theological work Speculum Speculationum (Mirror of speculations) set out in four books. The main thrust of Book One is to address the Cathar Heresy. In Book Four he discusses the subjects of grace and free will. One writer (R.M.Thomson, who edited a translation of the work) suggests that, relieved of educational demands, Neckham became ever more discursive in his writing, revealing his interest in both Platonic thought as well as his beloved Aristotle: it was not until Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) that the conflict between Plato’s philosophy and Aristotle’s was considered resolved.

Neckham also wrote in verse which was part of the 12th century interest in language stemming from the development in Latin scholarship. “Words and their meanings – and implications – were basic to any attempt to comprehend the world.” (Swanson R.N. The twelfth-century renaissance. University of Manchester Press. 1999)

Towards the end of his life he wrote Corrogationes novi Promethei (New Teachings of Prometheus) a long and uncompleted work.

The first part is concerned with the Monastic life. “The Abbot must be the teacher by precept and example. He must not be too anxious to fill the chests with gold.” Did the experienced Abbot Neckham, one wonders, accept the need for an appropriate level of concern to secure sufficient gold? In Part Two he writes of the need to avoid vices – which include becoming gloomy and the excessive use of candles, presumably for personal light rather than in the church. In the Third Part, Neckham writes of the ages of Man. “It ends”, writes Hunt (op cit) , “with an elegy on the loss of youth.”

1215 is one of the most famous dates in history as the year of Magna Carta but for the ordinary Christian person at that time, 1215 was of much more importance as the date of the 4th Lateran Council in Rome. It was at this Council that many matters were decided which impinged on the ordinary person’s life: the requirement to accept various doctrines, including Transubstantiation developed from Plato’s notion of essence and accidence, and other dogmas and to observe certain practices such receiving Communion at least once a year after Confession. It is indicative of Neckham’s academic standing that he was summoned to attend the 4th Lateran Council and an indication of his favour with King John that the King ordered the Bailiffs of Dover to provide Alexander with a properly equipped and staffed ship for the voyage. However, it seems likely that Neckham did not attend the Council as he wrote to the Bishop of Worcester that he was too ill to undertake such a journey.

“Through his prolific writing in many fields, his teaching at several educational levels, and his active participation in monastic life as well as royal and ecclesiastical service, Alexander Neckham was important in transmitting and transforming the widening intellectual interests of the twelfth century into their scholastic form of the late medieval period.” (The Middle Ages : Dictionary of World Biography: Volume 2. Edited by Frank N Magill Routledge and Salem Press Inc 1998).

Alexander Neckham died at Kempsey in Worcestershire, a Manor of the Bishop of Worcester, in 1217 – which means we not only commemorate 900 years since the founding of the Abbey but also remember the death of its most famous Abbot, 800 years ago.

Neckham was buried in Worcester Priory, now the Cathedral, where a brass plaque in his memory can be found, most appropriately, in the cloister. In translation it reads:

Wisdom suffers an eclipse. A sun is buried, which, while it lived, every branch of learning flourished. Neckham is dissolved into ashes. Had he one heir on this earth, his death would be less cause for tears.

< Part One – Medieval Manuscripts of Cirencester Abbey