Hi! I’m Emily, a Museum Studies M.A. student at the University of Leicester. As part of my course, I’m doing a summer work placement here at the Corinium Museum. My background is in Latin and Roman culture. While I’m here I’ll be doing a series of blog posts looking in closer detail at interesting features, themes, and ideas drawn from my explorations of the Corinium Museum’s collections. Enjoy!

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the UNESCO International Literacy Day, so this week I decided to look into literacy through time, and how this theme is represented in the Corinium Museum collections.

The earliest origins of writing as a form of communication are believed to come from the city of Uruk in Mesopotamia, and date to the late fourth millennium BC. Administrators in the city began to record accounts of the city’s food supplies by marking symbols into clay tablets. Similar techniques might have developed at around the same time in Syria and Turkey, although definitive evidence of this has yet to be found.

The first symbols that could be considered a type of alphabet originated in Ancient Egypt. By 2700 BC twenty-two characters had been developed which represented common syllables.

Sometime before the 8th century BC the Phoenicians developed a script which represented sounds, and had very few characters. This meant that it could be used to record several languages, and was relatively easy for traders to learn. The Phoenicians were advanced sea traders, and as a result this alphabet spread across the Mediterranean.

In Ancient Greece it was adapted to also contain vowels, creating the first true alphabet. A variant of the Greek alphabet developed into the Latin alphabet, which is used in England today, and spread through trade and the expansion of the Roman Empire.

The earliest writing in the Corinium Museum collection can be found on the Bodvoc coin, an Iron Age gold coin from the Dubonii tribe. On one side is inscribed the Ancient British name BODVOC in Latin script, and on the reverse is depicted a triple-tailed horse and eight-spoked wheel. The coin was found near Chipping Campden in 1981. This would have been a very valuable item, and it seems likely that at this stage literacy in Britain was confined to the elite of society.

In Roman Britain literacy seems to have been more widespread. Latin inscriptions are commonly found on monuments, tombstones, and even everyday objects like this brooch which reads ‘UTERE FELIX’, ‘use this happily’. Whether the craftsman who made the brooch was able to read and write, or whether they were copying a pattern cannot be certain. However, writing is so common on Roman artefacts that it makes sense to assume that a relatively substantial proportion of the population had some level of literacy.

Literary sources tell us that wealthy Roman children were taught to read and write at home by their parents or by slaves who were bought specifically to fulfil the role of a tutor. Older boys would then receive further education at school, when a teacher would deliver lessons to a group, probably in the marketplace (forum). These wealthy boys would be taught literature, history, mathematics, philosophy, and the skills they would need to be successful businessmen and politicians. Some wealthy girls would continue to be educated at home by tutors and their mothers.

The Romans taught children to write using wax tablets and styluses. Letters could be scratched into the soft wax with the pointed end of a stylus, and erased with the flat end. This method was far less expensive than the use of ink and parchment. A fragment of a wooden wax tablet was excavated in Cirencester in 1990, and is a remarkable survival. It is also surprising that the tablet was made out of oak, while other examples have used pine or fir.

Whether poorer Roman people and Romano-British people would have been literate, and the levels of their literacy, is strongly debated. Graffiti found throughout Rome and Pompeii suggests that large proportions of the population had some ability to read and write, although spelling and grammar mistakes are common. The large number of letters found at Vindolanda, on Hadrian’s Wall, suggest that there was a high level of literacy among the soldiers in the Roman army and their families.

At Cirencester excavations in Victoria Road in 1868 uncovered a section of wall plaster that reveals a Latin acrostic. In this word puzzle the word ‘TENET’ forms the shape of a cross, and the letters rearrange into the Alpha and Omega (A and O, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and a symbol of Christianity) and the phrase ‘PATER NOSTER’, meaning ‘Our Father’, the opening words of the Christian Lord’s Prayer. This clever puzzle was carved by hand into decorated plaster. This demonstrates some literacy on the part of the person responsible for the markings. The plasterwork, however, suggests that the find came from a relatively wealthy household.

Literacy levels seem to have declined after the departure of the Romans from Britain. Between 878 and 892 King Alfred the Great embarked upon an initiative to improve literacy levels for all. There is little evidence of how he went about implementing these reforms, and most successes seem to have taken place in religious institutions, rather than among common people.

It seems to have remained the case throughout the Medieval period that literacy was reserved for the rich and religious classes of society. The Corinium Museum, for example, is home to a Medieval silver-gilt pendant inscribed with the names of the Biblical Three Kings, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

Historical literacy levels are very difficult to measure. For the most part it seems that, in England, the working classes had little or no ability to read and write until some level of schooling became compulsory for all children in the late nineteenth century. Until this period, many people were even unable to write their own names, and many wedding certificates, birth certificates, and death certificates are signed with the letter ‘X’ instead.

When schooling did become compulsory, children would first learn to write using equipment which is very similar to the wax tablets used in Ancient Rome; a slate and chalk. Like the wax tablets, these tools were inexpensive, and the writing could easily be erased and corrected. There are many examples in the Corinium Museum’s social history collection.

After this point in history, working class voices and stories begin to be better represented in the Corinium Museum collections. Many documents such as letters, receipts, and posters have survived which give insight into the daily lives of the people who lived in Gloucestershire. This is partly due to the fact that in the twentieth century these objects began to be valued as historical evidence, when in previous generations they might have been discarded. However, is it also a sign that working class people were reading and writing in their daily lives, and were leaving behind a written record of their existence in a way which they never had before.

This diary, written in 1925 in an old receipt book, was found hidden behind a beam in a building in Cricklade Street, Cirencester. It was written by Nellie, a young woman who was living and working in Cirencester, and the entries detail her tumultuous relationship with her fiancé, the 35 year old Arthur. Writing was an important part of Nellie’s life, not only because she kept a series of diaries (some of which she destroyed, fearing that her family might discover them while she was away working in Great Yarmouth), but also because letters were her only way of communicating with Arthur whenever one of them had to work in another part of the country.

Writing, however, was not so important to Arthur, much to Nellie’s disappointment. She complained ‘And then came the time when I thought he never cared a rap, He was up Miserden, & I asked to write twice or three times a week, & he never used to trouble to answer. I used to cry nights over that. And then there was that awful row, when I thought that I was going to lose him. I shall never forget that never. I was bound to write to him & tell him that I couldn’t live without him & that I worshiped him for the better far better than anybody else in the whole world. But it showed what stuff he was made of, because he still stuck to me.’

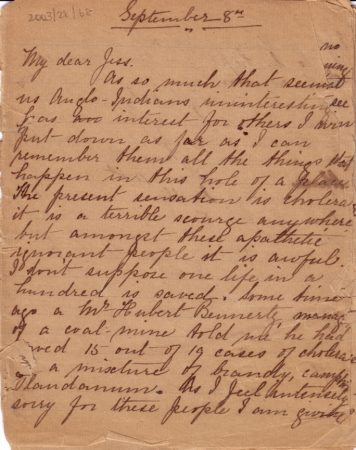

Finally, while searching through the collections I stumbled upon this letter. It caught my attention for the sole reason that it was written on today’s date, September 8th! It was sent from India, and the first four sides, addressed to ‘My dear Jess’, describe a cholera outbreak. The next eight sides are dated January and February 1913 and describe life in India. This perhaps means that the earlier part was written in 1912, in which case today is this letter’s 104th birthday!

Surveys of literacy levels in the UK have been taking place since 1948. Research carried out in 1997 found that overall literacy levels had changed little since 1948, with middling and high achieving students faring very well in comparison to international studies, but with large proportions of the population struggling. It found that, while few of Britain’s school-leavers could be described as illiterate, many lacked the levels of literacy necessary for success in adult life and work. According to the National Literacy Trust, around 16% of adults in the UK are ‘functionally illiterate’, meaning that ‘they would not pass an English GCSE and have literacy levels at or below those expected of an 11-year-old’. UNESCO is working to improve literacy rates among children and adults worldwide, and 8th September is a day for celebrating successes and campaigning for future progress!

Imagine what your life would be like if you couldn’t read or write. You’d miss out on these blog posts, and wouldn’t that be a shame?!