Our guest blogger Emily, a Museum Studies M.A. student at the University of Leicester, looks back at some of Britain’s earliest gold treasures in the Corinium Museum collection.

Since around 5000 B.C. gold has been used to create accessories and objects that symbolise wealth, status, and elegance across the world. Some of Britain’s earliest gold artefacts date to the Early Bronze Age, such as the Ringlemere Cup (1700-1500 B.C.) and the Rillaton Cup (1800-1600 B.C.), both of which are at the British Museum.

The Corinium Museum is also home to some fine examples of early gold objects. The Poulton Hoard, discovered in 2004 and 2005 in the village of Poulton, near Cirencester, dates to around 1300-1100 B.C. and consists of 67 gold and bronze artefacts. These were gold finger rings, torc fragments, and penannular (open) rings, and bronze tools which could have been used to shape, decorate, and cut the gold. This combination of objects suggests that bronze tools were used in early gold-working, and the hoard could be interpreted as a Bronze Age goldsmith’s standard trade tools. Many of these objects were unfinished or appear to have been deliberately broken before they were buried.

There are also two other Bronze Age gold objects on display in the museum’s Prehistory Gallery which were not part of hoards, but which are nevertheless beautiful and fascinating artefacts. One of these objects is a penannular ring which serves no obvious function. Rings of this type are sometimes called a ‘tress-ring’, believed to be some kind of jewellery, possibly for locks of hair, or ‘ring-money’, following the theory that they were worn on clothing or tied together and used as an early form of currency. The other object is a rare Bronze Age gold bead, found in Coberley in 2011 and acquired by the Corinium Museum in 2014. The bead was rolled into shape from a sheet of gold.

The skill with which objects such as these were made reveals that, although metalworking and goldsmithing were still in their infancy, Bronze Age craftsmen were highly capable and skilled in their handling of gold.

There are relatively few gold objects in the Roman collection. However, the Roman invasion of Britain brought with it the industrial mining and production of gold. Bronze Age gold extraction near Pumsaint in Carmarthenshire is believed to have been capitalised upon by the Romans in around 74 A.D., who established the only recognised gold mine in Britain. On display at the Corinium Museum are several gold earrings, decorated with agate, pearl and turquoise, and gold rings, one of which shows two clasped hands, symbolising marriage.

In recent years the Anglo-Saxon period has become well-known for its fine gold artefacts, thanks to the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009, consisting of over 3,500 objects, making it ‘the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork ever found, anywhere in the world’. All of these objects were connected in some way to warfare.

The Corinium Museum’s Anglo-Saxon gold, however, reveals more personal connections between these riches and the individuals who treasured them. On display are three ornate gold disc pendants, and a garnet and gold pendant which was originally part of a necklace with glass and agate beads. Two of these gold discs were found in burials. One, decorated with garnet (left), was buried with a 35-40 year old woman who was also laid to rest with a weaving batten. Another, decorated with glass (right), was found in the grave of a small child. Its decorative features are well-worn, leading to the suggestion that it might have been passed down between generations of the child’s family. The context of these finds show not only that they symbolised wealth and status, but that they might also have had some emotional and sentimental importance to these individuals or to their mourning loved ones.

In 879 A.D. the Viking ‘Great Army’ travelled across the Cotswolds and settled for a year in Cirencester. Although there is little physical evidence of these events, the Corinium Museum is home to a few objects which show Viking influence, including a plaited gold ring dating to the 10th century, and an 8th-11th Century decorated gold button. These are very finely made and decorated, in keeping with the high quality of Viking craftsmanship.

In the Medieval period Cirencester had a prosperous wool trade, and in 1402 the Cambini of Florence wrote that Cirencester had the best wool market because it had an exchange for Florentine gold coins. The Corinium Museum collection includes a 13th century gold brooch showing a rampant lion, and a gold quarter noble coin from the reign of Edward III (1327-77).

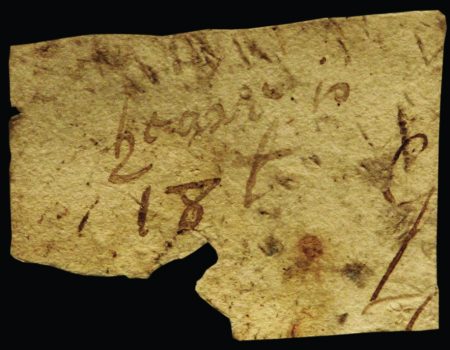

The final gallery in the Corinium Museum addresses Cirencester and Gloucestershire’s role in the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). In this gallery is the Weston-sub-Edge Hoard, a collection of 307 silver coins and 2 gold coins which were found in 1981 under the floorboards of the ‘Hall of Friendship’ village hall in Weston-sub-Edge, which had been a barn at the time of the Civil Wars. The coins had been hidden in a custom-made lead pipe, and were accompanied by a note which read ‘hoard is £18’. The most recent coins in the hoard date to 1642. The hoard is a sign of how the turbulence and unrest of this period impacted individuals, and offers a very human connection to a defining moment in history.

The 1996 Treasure Act means that ‘all finders of gold and silver objects, and groups of coins from the same finds, over 300 years old, have a legal obligation to report such items’. Reporting historical finds ensures that their significance can be better understood, that the finds and the findspots can be protected, and that further investigation can be undertaken if necessary. Detailed advice is available on the Portable Antiquities Scheme website.

Gold has been highly valued in Britain for thousands of years. Let’s hope Team GB can bring home some more!

This blog was written by Emily Tilley, a Museum Studies M.A. student at the University of Leicester.